Lessons from a Pandemic: 2. Which science exactly?

[London, 13 May 2020]

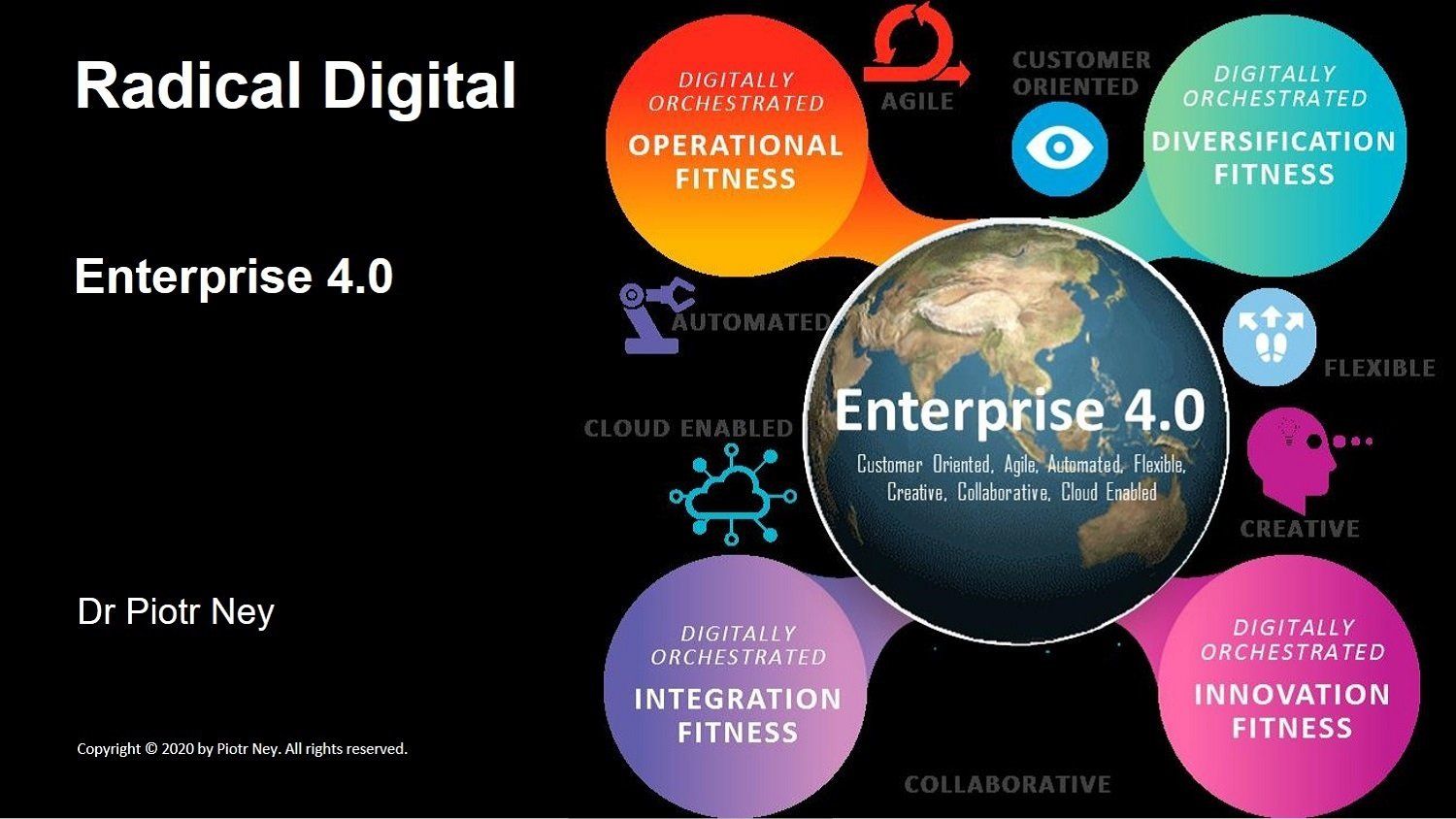

The tragic global outbreak of covid-19 has already taught us many severe lessons in pandemic preparedness and response. Rapid innovation and product TTM, distributed collaboration, infection modelling, additive manufacturing of personal protective equipment (PPE), artificial intelligence (AI) powered vaccine and anti-viral drug development and clinical trials, sharing of real-time research data, scenario modelling and contact tracing. All of these elements, and many more, harness the power and the universal ubiquity of digital. Digital technology is thus at the heart of our fight against the virus.

I hope that, post pandemic, the lessons learnt from this pandemic will persist and a global, shared architecture of advanced digital competencies is permanently established to support more effective collaboration, innovation and a quicker response to better defeat future pandemics, biothreats and other worldwide catastrophes.

In the previous article, I praised the rapidly self-organising, open and global collaboration of scientists to fast-track therapeutics and vaccines to the market. In this second article of this series, I argue that our Government’s claim that Britain’s centralised response to the pandemic is purely science-led is dangerous nonsense. It shrouds Government policy with a cloak of false legitimacy and it inhibits us from taking individual responsibility for our safety, and from openly debating some critically relevant societal issues and trade-offs.

Beyond the smoke and mirrors

The UK’s lockdown exit strategy, a phased approach to reopening workplaces, schools, gyms, services and shops, is still being formulated. Although the Government admits that we are facing an unknown antagonist, we are assured that each policy step is carefully calibrated in line with latest scientific advice. We are in turn obliged to play our part, such as accepting an increased level of social surveillance, maintaining social distance, wearing PPE or submitting to testing. Yet the claim that our national response to the pandemic is some finely refined scientific endeavour does not hold up to any serious scrutiny.

We are trying to understand and tackle covid-19 through a complex blend of inductive interpretation and hypothetico-deductive scientific methods. The first involves us harvesting as much of the quantitative and qualitative data, which could be significant, as we can. As a researcher myself, I have learnt to always collect a wider-than-first-assumed scope of data, to be on the safe side. Subsequent inductive analysis often shows up surprising patterns and correlations with data sets outside the boundary of what we thought would be the core data. Could covid-19 mortality be linked to an individual’s diet or the weather? Probably not, but let’s throw in the data anyway!

This data is then tagged, coded and structured into meaningful categories and relationships. Insights and sometimes surprising correlations start emerging, and are then validated through further research, for example to determine which correlations are in fact causations. This is a pure grounded theory-driven scientific approach, which was popularised by two sociologists, Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss, and derived from their study of dying hospital patients in 1965.

But we are not exploring covid-19 in a theoretical vacuum. Science already has much experience of disease control and specifically of hundreds of other coronaviruses. These are already a scientifically well-researched family of pathogens, which range from those that cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold, through to recent ones that emerged from animal reservoir spillover events, and can cause acute and widespread illness and death.

SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) emerged in 2002, followed by the Middle East (MERS) respiratory syndrome caused by the MERS-CoV coronavirus in 2012. We have sequenced the DNA of covid-19 and now harness the power of bioinformatics, cloud supercomputing and digital collaboration around the world, to mass screen and identify possible antigens. Based on our extant knowledge and experience, scientists can rapidly test hypotheses and focus further research in directions that offer most hope. Hundreds of drugs are being explored or already trialled and more than 4,000 peer-reviewed research articles have already been published this year.

Yet some fundamental questions about covid-19 remain a mystery. According to the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), “We remain pretty much in the dark regarding the nature of immunity, the pathogenesis of disease, optimal diagnostic tests, its transmission pathways and duration, and appropriate prevention, treatment and vaccines”.

Thus we are in the middle of a global research race. Insights from the field, the grounded research data sets, which tell us what is happening in real life, are blended with our existing scientific knowledge and hypotheses, the what should be happening in theory, and comparisons and contrasts between the two analysed.

An example challenge of critical importance to any pandemic response policy, is an understanding of why individuals respond to the covid-19 virus in such vastly different ways. Many presumed correlations are being overturned. Counterintuitively, asthma sufferers do not appear to be among the most vulnerable, even though covid-19 typically causes respiratory tract infection. Even more peculiarly, tobacco smokers seem globally to be considerably safer from severe covid-19 infection, even as their handling and smoking of cigarettes should in theory make them more susceptible to absorbing a higher viral load. There are several possible explanations, a key one being nicotine’s binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) cell-member proteins, which restricts covid-19 from doing the same, thus blocking its access to cells. Nicotine may also help in some patients by helping to limit cytokine storms, hyperactive immune responses.

Terabytes of complex, heterogeneous data are thus being generated and analysed globally. Extensive data mining and AI-powered insight tools churn this data in our shared global cloud 24/7, to identify patterns of infection spread, comorbidities, correlations with demographics, population densities and movements, and thousands of other significant factors.

The core public message is that we collectively need to reduce the R number and "flatten the curve". The magical R is the effective reproduction number, which indicates an infectious disease’s capacity to spread. It simply shows the average number of people that one infected person will in turn infect. Thus if R is kept below 1, the disease will in time peter out in the population, at a rate inversely proportional to R. For example, if R=0.9, it would take four months to drive the number of daily infections from the current 20,000 down to a more manageable 2,000. If R=0.75, it would take just seven weeks. Without a reliable national testing programme to validate it, even Sir Patrick Vallance, UK’s Chief Scientific Advisor, admits that it’s a rough estimate derived from a variety of sometimes conflicting and unreliable data, and mathematical modelling.

Even allowing for its questionable reliability, it may be useful to adopt one clear headline indicator such as the R number to drive behavioural congruence in the public. So far so good. We agree to accept our shared goal. But how do we collectively get there? The Government’s messaging on this is far from clear. Daily media briefings have become a distracting blend of General Melchett style bombast, platitudes, hyperboles, pseudo-scientific concepts and much smoke and mirrors. As Jeremy Warner wryly observed recently in The Telegraph, hardly a Tory-bashing title, what we are seeing from our Government is salesmanship in lieu of leadership. The recent lockdown exit roadmap presented by the Prime Minister (PM) is so full of inconsistencies and logical holes, that one can drive a fleet of ambulances and hearses through it.

Holding the data up to scrutiny

The British public are not given access to any meaningful meta-analysis of what specific scientific data the Government is basing its guidance on. SAGE, together with several other acronyms and individual experts, provides scientific and technical advice to Government, which it is not bound to follow. There are some obvious tensions and gaps between what “the science” advises and what our executive branch then announces and decrees.

The trouble is that we can’t scrutinise these trade-off discussions between the experts, public servants and politicians, as these are happening behind closed doors. SAGE and Cabinet covid-19 briefings are conducted in obsessive secrecy, outside of any possible challenge by Parliament or any peer review by a wider circle of experts and scientists, let alone full public scrutiny.

Jeremy Hunt, the former Health Secretary, said “At fault is a systemic failure caused by the secrecy that surrounds everything that SAGE does”. So why such secrecy? I empathise that many people could be willing to take the Government strictly on trust, but there is an army of people in this country and beyond, me included, who could help to validate the underlying data and the insights and assumptions derived therefrom, and collectively hold the Government accountable.

Well beyond infection and mortality reporting and the R number, the public needs to understand the specific data that justifies the various elements of the pandemic public policy. What specific scientific evidence is there for lifting individual restrictions or recommending specific actions?

Examples there are plenty. The Government has announced that from today, higher fines for people who break social distancing rules will be enforced. Two people from different households in England can meet outdoors, for example in a park, as long as they stay more than 2m apart. Why not three people? Why not 1.5m providing they wear face coverings? It’s reasonable that simple and unambiguous directives may need to be given to those who just want and need these, but a sizeable segment of the population should not be too intellectually stretched if the Government were to share the underlying evidence.

Domestic helpers and childminders are allowed to enter our homes every day, but personal care services, such as hairdressers, will not be allowed to reopen on 1st June, because despite precautions such as disinfecting their work station between clients and using PPE, “there is a higher risk of virus transmission”. What’s the evidence? Garden centres are allowed to re-open in England and Wales, but they are accepting card payments only. Show me the evidence for the additional risk of handling cash. The list goes on.

Employers, unions, including the National Association of Headteachers (NAHT) and the National Education Union (NEU), as well as the public, are demanding clear, scientific published evidence and an explanation of how “the science” supports specific Government advice.

Vague and imprecise slogans such as “stay alert” have been criticised by Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s First Minister, and many other politicians of all shades as being meaningless in practice. “People are now justifiably confused”, said Steve Reicher, professor of social psychology at the University of St Andrews, and a behavioural adviser to the Government. Even SAGE reports that “”control the virus” is similarly an empty slogan without an indication of how to do this”. It then advises that, “For government communications to be effective in promoting adherence to guidance and in avoiding confusion, anxiety and distrust, they need to be clear, precise and consistent. This includes being behaviourally specific, i.e. advice as to who needs to do what in what situations, and what should not be done. Advice should be closely linked to action”.

Thank you SAGE, and yes please Boris!

Digital baloney

We are told to trust the guidance because it is science-led and based on reliable and objective evidence. This is baloney. Which science, exactly? Even within the Government’s inner circle, scientists (and remember that these represent a number of disciplines, such as epidemiologists, clinicians, statistical modellers, behavioural and social scientists) disagree on some of the key assumptions and decisions.

The world of science is, and always has been, a cacophonous scramble of competing egos, rival projects, and a constant struggle for prestige and to secure funding and resources. Life sciences particularly are an ongoing dialogue. Scientists explore, hypothesis, criticise the work of others, argue and, thankfully, often do collaborate with likeminded peers. It is natural that, given the wide range of backgrounds and experiences, different cognitive and heuristic biases, different ontological and epistemological perspectives, and their different work contexts (political, academic, funding), sensemaking by scientists even when presented with identical data would be different. Consensus in science advances through dialogue and a lot of conflict, to paraphrase Thomas Huxley, as beautiful hypotheses are regularly slayed by ugly facts.

The observation that while scientific data is universally shared, individual countries (even within the UK!) have embarked on sometimes very different response strategies, is in itself indicative that scientific evidence does not translate directly and rationally to policy making. Take Sweden, which made starkly different predictive assumptions based on the same data and chose not to follow a strict, UK-type lockdown policy. It now has a lower covid-19 death rate than the UK. Although its population density is lower than the UK’s, we still do not fully understand the explanation.

The Government’s response may be evidence-influenced, but it is essentially a political process to arrive at some acceptable, politically expedient consensus. I suspect that the belated rush to UK’s rigid lockdown was a product of trying to make up for the Government’s indecision and critical inaction during the first few weeks of the outbreak, when the infection footprint doubled in size with every three days of political prevarication, as well as its desire to show that it is now taking the pandemic seriously and (unhelpfully in contrast to Sweden) taking some decisive action.

The Government and its advisers find themselves firmly in the cognitive domain of bounded rationality. Rather than hard-evidence grounded and optimal assumptions and decisions, they necessarily make satisfactory ones. It does not help that only around 26 of 650 British MPs have a science degree, a striking 4%. Graham Medley, the chair of one of the critical SAGE subcommittees (SPI-M), has publicly commented on the “policy science gap”, with experts trying to explain key epidemiological concepts to ministers being met with “blank faces”. Our PM has a noble background in Classics. Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, studied PPE, as did his predecessor, Jeremy Hunt. In this context, sadly I do not mean that they studied the masks and gowns which are still in such short supply, that the Doctors’ Association (DAUK) are now demanding an open public inquiry to investigate the Government’s failure to provide front-line NHS and care staff with timely, adequate equipment.

It may also not help that at least 16 of the 23 known members of the secretive SAGE are directly employed by the Government and therefore have a clear potential conflict of interest and an ongoing concern over their personal career security.

Public policy is constrained by the complexity of the problem, unreliable data, conflicting scientific inferences, cognitive limitations and the time available to formulate it. It is then additionally and significantly modified by considerations such as its economic and budgetary impact, its fit within the Government’s overall policy agenda, assumptions about how the general public and other stakeholders (Parliament, employers, unions, the media, other countries) are likely to react and a huge dollop of pragmatism, such as how compliance with the prescribed restrictions could effectively be policed or otherwise enforced.

The eventual Government policy is thus a product of secret trade-off discussions and stakeholder consultations, much whiteboard satisficing, and political pragmatism. No wonder that so much smoke and mirrors are needed to present it with a straight face in the media briefings. New acronyms, such as the Joint Biosecurity Centre (JBC), are additionally being created to give us an illusion of progress and additional security. And it’s all strictly based on science, trust us!

Enough! I invite our Government to give us the critical data and to trust us, the people, to understand it, its reliability and other evidential limitations, and then use our common sense to make informed decisions, appropriate to our particular circumstances.

The public also understands that as a society we have limited resources and structural limitations. If Britain cannot fully finance a specific intervention, or it would have an unbearable impact on our economy, or we cannot source sufficient kits for a testing-led strategy, because we have offshored much of our life sciences production to other countries and now have to rely on imports, let’s have these discussions in the open. People get it!

Devolution of the response

I also advocate the delegation of covid-19 monitoring and response to local and community levels. Britain could do a lot worse than reimport Thomas Jefferson’s belief in the power of the people when faced with partisan divisions, economic uncertainty, and an external threat. Jefferson, a champion of individual liberty, was a great believer of delegated power. Communities when given accurate information, and adequate resources and support, are best placed to formulate their own responses, which take into account their unique circumstances.

Centralised, top-down planning disempowers individuals. At a time of crisis, it is often simply not responsive, agile and focused enough to control the dynamics, such as the virus spread, on the ground. It doesn’t make much sense imposing exactly the same covid-19 lockdown exit strategy on the Cotswolds as on London, or even individual communities within it. Well informed communities and individuals need to take responsibility for local responses.

This devolution needs to begin by reporting the R number, and other key indicators and trends, at the community level, not as a meaningless national aggregation. The R number is not an actionable insight at the national level. It masks huge geographical, demographical and contextual variations, such as disproportionately high levels of infection in care homes.

Mark Woolhouse, a professor from the University of Edinburgh and a former adviser to Tony Blair’s government during the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak, says of the R number that “it is a very, very crude” indicator. Greg Clark MP, the Chairman of the Science and Technology Select Committee, agrees that the national R number is largely irrelevant. A panel of experts led by Sir David King, the Government’s former Chief Scientific Adviser, set up as an alternative to SAGE, is calling for pandemic modelling and response calibrations to be performed at local levels.

As we enter into the exit phase, this makes perfect sense. Different towns and communities are likely to peak and experience further waves of the pandemic at different times and to different degrees. The UK needs a local R number based approach, within the framework of the Government’s national guidelines, and supported by centrally distributed resources. Yet when challenged to provide regional and contextual R numbers at a recent media briefing, Professor Stephen Powis, the National Medical Director for England, told the press on behalf of the Government that this was not possible. When the PM was asked to publish the scientific evidence and advice by the Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer only yesterday in Parliament, Boris adroitly sidestepped the question with a vague “in due course” affirmation.

Which science, which data?

Let’s take data quality as the one of the most obvious indications that policy is far from being science-led. Several leading experts, such as Professor Tim Spector, a genetic epidemiologist at King’s College London, estimate that around two thirds of covid-19 infections are not diagnosed and thence missed from the Government’s statistics. This side of widespread and statistically robust testing of the population, we simply do not know. A leading statistician, Sir David Spiegelhalter from Cambridge University, Professor Peter Horby, chairman of the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (one of the several acronyms advising Downing Street), and several other renowned experts, have publically attacked the “extraordinary failure” of the Government to prioritise mass random testing that would give us an understanding of true infection spread and the proportion of asymptomatic carriers.

Without such fundamental facts, any decisions around the exit strategy are based largely on guesswork. Sir David himself estimates that based on an average death rate of 1%, it is possible that already 3.5m people are or have been infected with the virus. Even Jeremy Hunt has been quoted as saying that Britain’s decision to abandon mass community testing in early March, in stark contrast to testing-led containment strategies of say South Korea, will haunt us.

The Government’s tracking and tracing app, which is being trialled on the Isle of Wight, is based on self-reporting of symptoms, as opposed to test results, which implies it will give highly inaccurate results, as many infected can remain asymptomatic for days or even altogether (I will shortly discuss this app and other digital solutions in more detail in another article in this series).

Let’s move on the mathematical modelling that shapes the above (inaccurate and incomplete) data into actionable insights. The Government relies mainly on two predictive modelling teams. The first is from Imperial College London, headed by Professor Neil Ferguson, who has just recently retired from SAGE for, ahem, personal reasons. The second is the Oxford University team, led by its professor of theoretical epidemiology, Sunetra Gupta. Both are conceptually similar, and based methodologically on the same SIR segmentation (susceptible, infected, recovered) of the population. Yet there is a gaping disparity between the scenarios generated by these two models.

This does not surprise me. Such models churn multiple key variables, which are based on informed and validated assumptions, where the scientists can make these, but guesswork in many other cases. A slight modification in these variables does often have a significant impact on the outcome.

I hope that it won’t be ungallant for me to also point out that previous pandemic models produced by the Imperial team subsequently proved to be spectacularly wrong. They predicted up to 136,000 deaths from bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease. Government intervention largely based on their advice led directly to the largely unnecessary culling of millions of animals, the European Union (EU) in 1996 banning exports of British beef for ten years, and stigmatised Britain’s food safety reputation for a generation. Ferguson’s models later predicted that up to 65,000 people were going to die from swine flu in the UK in 2009, whereas while still grim, the true tally stopped at fewer than 500 deaths.

The Imperial College modelling methodology and underlying assumptions have one thing in common with most of the other models, in that these have never been formally peer reviewed by the scientific community. When Edinburgh University repeatedly ran the Imperial College model, each time with the same input set of data and parameters, the algorithm would produce different results. Why have these mathematical models upon which our lives depend, in a very real sense, not been placed in the public domain? An open source paradigm would allow these models to be scrutinised and improved.

To construct critical public policy, with public health, £-billions of cost to the Treasury, and millions of jobs at stake, on code that has not been externally validated and is allegedly “deeply riddled with bugs”, especially given the poor track records of the team cranking its handle, seems like breathtaking folly. The Government, in its panic to suddenly spring into action, desperately adopted these models as “the science” unquestioningly, and have been using these as a figleaf to justify its policy decisions ever since.

We are aware that even a slight difference in the estimated R number, for example, once multiplied across the whole UK population, will result in dramatically different pandemic profiles. Other key parameters, such as susceptibility (especially in correlation with demographic factors, such as age), infectivity, comorbidities, assumptions around causal pathways and how long those who have recovered from the infection are then protected against subsequent infection, and the reliability of the current throat/nose swab testing, are similarly unclear. A wide range of assumptions for each of these and other factors could be justified by different scientists.

The lack of robustness in predictive modelling is not unique to Britain. Thomas McAndrew, from the Massachusetts University, who monitors covid-19 modelling from various teams across the US, reports that some expert teams admit to their models being up to 80% the result of intuition and personal assumptions of the researchers, rather than auditable and validated evidence.

Having acknowledged the perils of overreliance on just one or two sources, SAGE now has engaged five distinct mathematical modelling teams, collectively named SPI-M, who estimate the national R number. Graham Medley, the chair of SPI-M, has admitted that, “At the moment, we’re having to do it by making educated guesswork and intuition and experience, rather than being able to do it in some semi-formal way”. SAGE then massages these ‘guesstimated’ numbers together to arrive at one headline number to present to the Government.

Some integration of models and metamodeling, at the UK and international levels, is also being currently pursued. A Royal Society initiative led by Professor Mike Cates of Cambridge University is connecting modelling teams across the UK into a collaborative network. This could produce more statistically reliable outcomes through averaging and challenging any egregious outliers, but does not inevitably compensate for poor data quality and untested assumptions.

Be careful what (data) you wish for!

The Government is already wrestling with some significant moral and ethical quandaries, such as how best to allocate and ration currently limited resources, such as PPE and testing kits, to the various cohorts in need. Similar trade-offs will need to be made if we are to flex restrictions for different cohorts of the population.

If science tells us one thing clearly, it is that some segments of people are at much more risk of severe illness and death from a covid-19 infection, compared to others. Thus if the pandemic exit strategy claims to be “science-led”, then logically stratifying the population and imposing differentiated restrictions and obligations, proportional to the risk profile of each cohort, would be a sensible, rational and evidence based policy.

Really? To remind ourselves, covid-19 discriminates in Britain mainly by;

- sex (male mortality rates are typically more than 50% greater than for females);

- age (the vast majority of deaths have been in people aged over 65 years);

- ethnicity (black people in England are nearly twice as likely to die than white people, according to the ONS, even after accounting for age, deprivation, location and underlying health conditions);

- wealth (a recent ONS study measured the mortality rate in the most deprived areas of England as 55 deaths per 100k population, compared to 25 deaths per 100k in the least deprived areas); and

- obesity (overweight people hospitalised with covid-19 are 40% more likely to die than slimmer patients (it is thought that excess fat cells produce high levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which assists covid-19 to bind and infect cells).

So if we agree on a sensible, rational and evidence based policy, one that is truly risk and science led, our stratified, phased exit strategy needs to impose selective lockdown restrictions. It will need clearly to discriminate on the basis of sex, age, race, wealth and BMI. And promote smoking.

Good luck Boris with selling that to the British public!

However, political correctness should not restrain the Government from engaging in a sensitive, clear and culturally appropriate way, with these high-risk cohorts to spread awareness of their elevated risk, dispel misinformation, which is particularly rife in some of these communities, and provide such focused support, advice and resources as are required to ensure they are not falling behind the pandemic curve.

The flipside of this perspective is that an individual can justifiably argue that their rights and liberties are unfairly constrained by them being statistically lumped together with higher risk cohorts in a national, one-size-fits-all approach. It is a reasonable point, one that should not be simply dismissed as some reactionary frustration. Any limitation of liberty needs not only to be proportional to the societal benefit, but also proportional to the needs and wants of specific individuals. This implies that, say, young, healthy, white smokers should not be ‘penalised’ because the others, the old, overweight, black non-smokers are disproportionally contributing to keeping the national R number and death rates high.

There are no easy answers. But such ethical, moral and economic arguments are the foundation of our society and we all need to be engaged without prejudice in such uncomfortable, but essential dialogue.

A glimpse into the shadows

“On 4 May 2020 a 13-strong committee convened by former UK government Chief Scientific Adviser Sir David King discussed some aspects of the science behind the UK strategy in a two and a half hour meeting. Leading experts in public health, epidemiology, primary care, virology, mathematical modelling, and social and health policy, raised ideas and issues for consideration which we are pleased to share”. So reads the preamble to SAGE’s “COVID-19: what are the options for the UK?” report published just yesterday. It sets out “recommendations for government based on an open and transparent examination of the scientific evidence”. Better late than never!

Helpfully for the Government, the report shies away from addressing “the clear structural and procedural weaknesses that contributed to the current situation as we expect these to be addressed in a future inquiry”. Phew! Having bought the PM some time then, it then criticises the ambivalence of the Government’s ongoing response, with its primary objectives of “flattening the curve” and ensuring that the NHS front line is not overwhelmed. It calls additionally for an active suppression strategy.

It agrees with my and others’ opinion that national pandemic indicators are useless in practice, and “real time high quality detailed data about the pandemic in each local authority and ward area”, and a devolution of response calibration to communities is needed. It suggests that a devolved social distancing and surveillance policy, based on local prevalence estimates and a special focus on high vulnerability and institutional settings, is likely to more efficacious than a centralised approach and better support real-time policy making. It adds that, “communities and civil society organisations should have a voice, be informed, engaged and participatory in the exit from lockdown”.

The report criticises the Government’s selective and misleading use of data in its smoke and mirrors sessions, and urges all involved to adhere to the Code of Practice for Statistics. Blimey, to think that to-date I always trusted Downing Street to adhere to these as a matter of course! In case you have forgotten its details since you last read it, the Code stipulates trustworthiness (confidence in the people and organisations that produce the data), quality (validated data sources and analytical methods) and value (statistics that directly support our needs for information). “It is vital the public has trust in the integrity and independence of statistics and that those data are accurate, timely and meaningful”, notes the report.

In summary

Until reliable, safe and long-lasting vaccine is universally available (think years, not months), covid-19 is likely to become endemic in Britain, persisting at low levels, with periodic localised breakouts. According to the World Health Organization’s chief scientist, Soumya Swaminathan, it could take “four or five years” to bring covid-19 under control and the pandemic could “potentially get worse”. Even an effective vaccine may prove not to be the ultimate get out of jail free card, as the virus could in the meantime mutate into new and potentially even more deadly strains.

This means that covid-19 will remain a part of our daily lives for the foreseeable future, and it will continue to exert a profound impact on our freedoms, behaviours, jobs and the economy.

For society to subscribe to this new ‘normal’, we urgently need to openly debate the scientific evidence and political trade-offs, which are currently analysed in secrecy. If we understand the projected impacts (economic, social, individual) and benefits of the various lockdown strategies and restrictions, and their scientific justification, we can arrive at some societal consensus, a new social contract.

Disturbing choices will need to be made, such as how many people we are willing to let die to accelerate our exit strategy. The Government saying that its principal motivation during the pandemic is to minimise deaths is glaringly disingenuous. If this was the case, we would remain in full lockdown until the pandemic fully peters out. Every relaxation of restrictions results in incremental deaths. The truth is that for economic, social and a wide range of other reasons, our exit strategy needs to be based on an agreed “acceptable rate of deaths”. What Downing Street considers this to be, is currently the Government’s secret. Such trade-offs need instead to become enshrined in a clear, understood, and explicitly accepted public compact.

Transparency, the placing of evidence and justification of policy decisions under parliamentary and public scrutiny and discussing policy trade-off is a fundamental principle of the social contract that underpins our liberal democracy. A government that avoids such scrutiny under the pretext of being mandated by science, while constraining individual liberties, plays a very dangerous game. Sooner or later, it is likely to be exposed by a public inquiry. In the meantime, it risks burning through much of its political capital and legitimacy. Paul Goodman, writing today in conservativehome.com, already reports of an undertow of doubt about the Government’s competence washing through the Tory party. Ouch! As per Abraham Lincoln’s dictum, “you cannot fool all the people all the time”!

I will specifically discuss the social contract perspective on the Government’s current handling of the pandemic in the next article in this series.

Dr Piotr Ney is an energetic promoter of innovation, digital transformation, customer and operational excellence, and sustainability, with some thirty five years of change leadership, consultancy and senior executive experience. He has an MBA in International Business and a PhD in Economics and Management, lectures part-time in Innovation Management and Disruptive Strategy and is a popular speaker at global business events. Piotr works in London and internationally as an independent consultant and educator.

Copyright © 2020 by Piotr Ney. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be published, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author.